I’m not a very good writer. I dedicated most of my past years to studying and improving – in terms of media, modernity left me long ago. I lack the necessary exuberant words, wit and will to review, or even properly describe the media I like, mais j’essaie. I consider my writings a seed, a torch which another Prometheus will take, while I sit here satisfied with merely the corny ancient metaphors and mythical allusions I always use. Yet I keep writing because Prometheus never comes. Welcome to my blog.

The day before I wrote this gave me a moment of artistic genius which evaporated as soon my exhausted corpse hit the bed. Hours before, I watched the movie Only Yesterday – the movie supposedly being reviewed at the moment. It’s a Studio Ghibli movie written and directed by Isao Takahata – like Grave of the Fireflies three years prior. It’s also a very different movie compared to its ancestor. In Only Yesterday, almost nothing notable happens – no war, no bombing, no dying. The most violent scene involves a single slap, the most action-packed scene involves mere running in the rain. Most scenes describe tasting pineapples, using fertilizer and dividing fractions. Yet, it impacted me as much as Grave of the Fireflies.

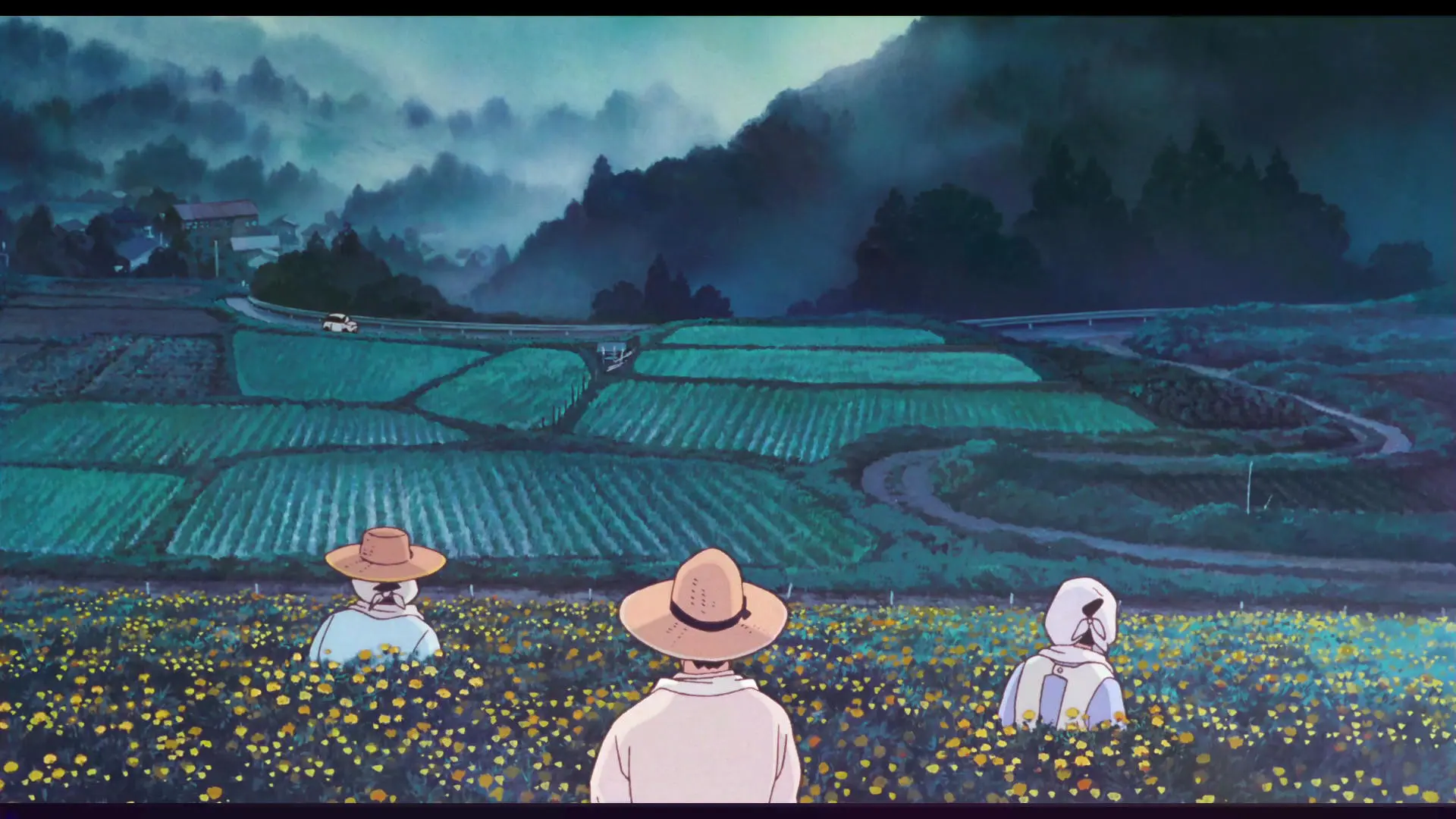

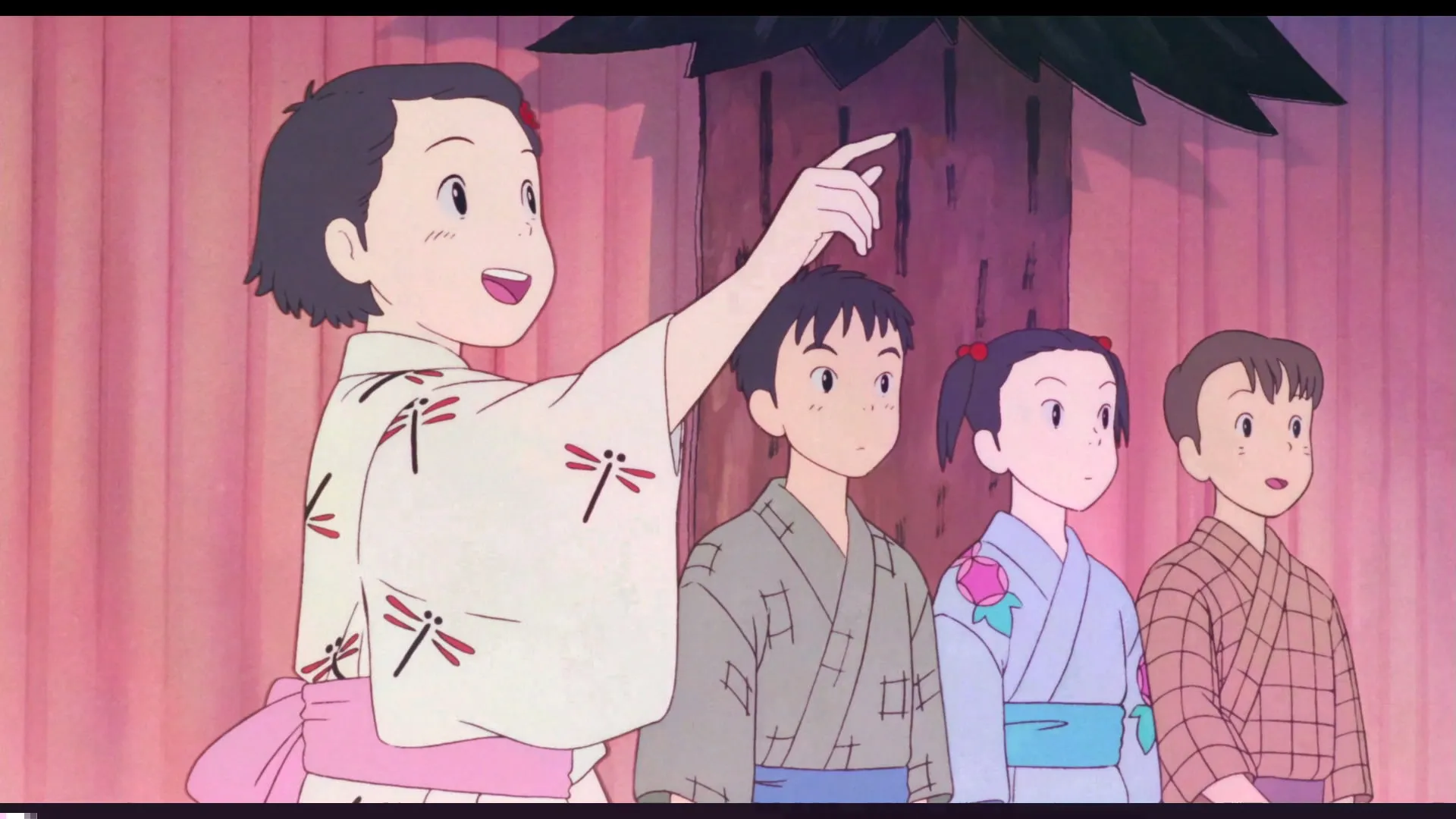

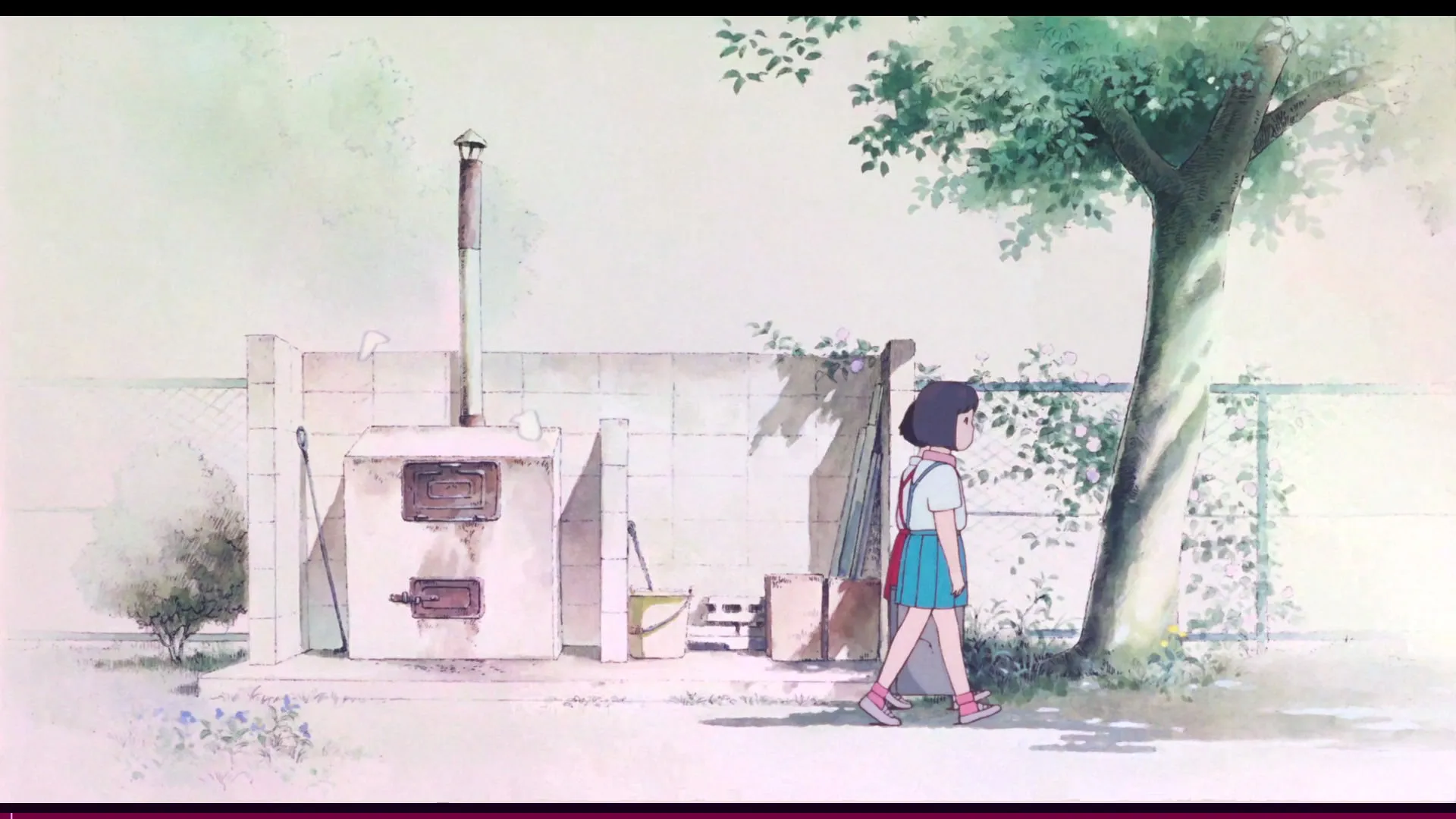

I’ve luckily never experienced war, but I’ve experienced lonely city life, working on a farm, school drama, arguments over grades and bickering with siblings. I’ve also thought about living beyond the city and without technology, and as such I’d say that Only Yesterday was just as poignant as Grave of the Fireflies. However, it is a profoundly boring movie for a modern audience. Many scenes contain no music, some have even no background, yet they all still have the Ghibli quality – you can take a screenshot at any single point and you’d get a beautiful desktop wallpaper. The style is still the same unmistakable Ghibli mixture of William Turner, surreal impressionism and introspective expressionism. Scenes often avoid contrast, and naturally the countryside scenes are very green and lively, while the city scenes are quite dull and lifeless. In the city, the most color you’ll get to see is a Coke vending machine. It’s not a movie someone used to action would like at all – in a way, it demands a lot of audience participation. The scenes with white backgrounds, likely symbolizing Taeko’s fading memories, want you to add in your setting – your school and home and friends and family. When there is no music, your soundtrack is playing. Taeko’s story is also your story.

The presence of Eastern European folk music in the nature scenes fascinated me. I presume that we are just as exotic to Japanese audiences as Japan is to us. The Hungarian, Bulgarian and Romanian melodies in a beautiful Japanese countryside setting were likely chosen to emphasize the dissonance and distance between city life and country life. All of the other music in the movie consists piano melodies which evoked an image of me sitting in a warm apartment room observing the afternoon rain while wistfully looking at a pianist in an apartment opposite mine, by an open window, loudly practicing her Arabesques. Is this all modern life has to offer? Why does she never appear next to me? This movie’s subtitle should simply be “Lent et douloureux”.

The difference between Taeko and other Ghibli heroines also fascinated me. Taeko is introspective, hesitant, timid – it’s obvious that this is not a movie by Miyazaki. She isn’t anyone special in the story, and actually changes by the end – unlike Miyazaki’s heroines. Often, she doesn’t know the right words to respond with, she’s even considered stupid by her family and we even discover her being unmarried at the age of 27 – something she insists is normal in Tokyo. In the scenes where Taeko is in the fifth grade, she looks almost identical to all of her classmates – she even tries to be just like them. Her father crushes her theater dreams, her mother scolds her for her apparent stupidity and eventually she grows up to be an office worker. Unfortunately, Japan is often depicted as this dystopia of office workers with crushed dreams and no stories worth telling. Yet, from what I know, life tends to be like that in most countries nowadays. City life is too comfortable to try and struggle against, which is the only war in this movie, and one which Taeko wins. She actually weighs the benefits and drawbacks, considers her current position and what life could look like, and makes an informed decision while having experienced both alternatives – she is an adult who chooses to live a more primitive life entirely on her own, and appears satisfied with her final decision. At the same time, I analyze her in a heated room with two massive monitors around me, on a keyboard with all the colors of the rainbow, my world being closer to Lain’s than Taeko’s.

The only lesson I got from this movie is that I need to think more like an adult and about adulthood itself. Any analysis of it is an analysis of the author’s own life. I didn’t need that lesson, but I did enjoy the movie. However, I think that it needs to be enjoyed at a particular period in life – approximately mine.