Artillery and math

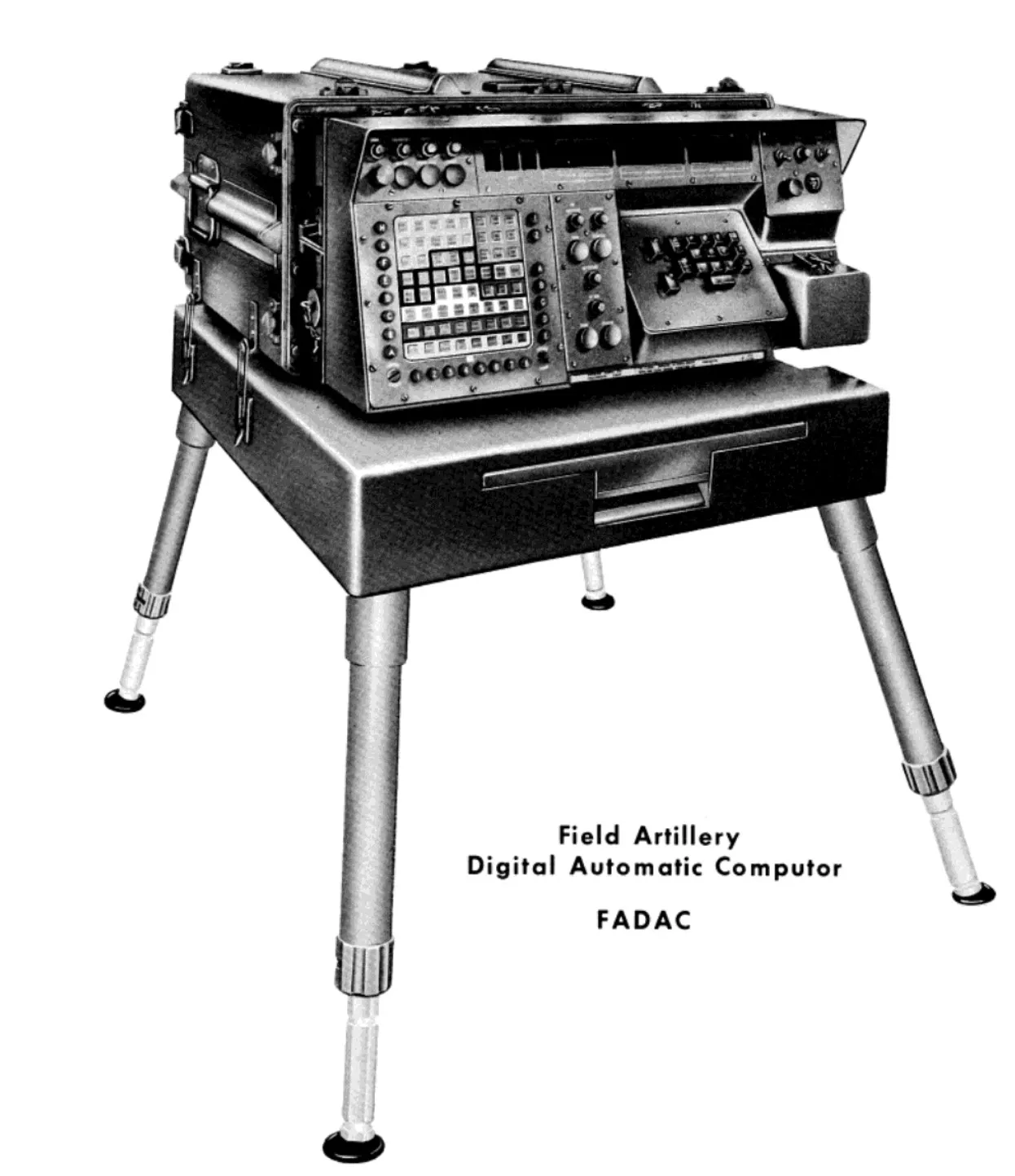

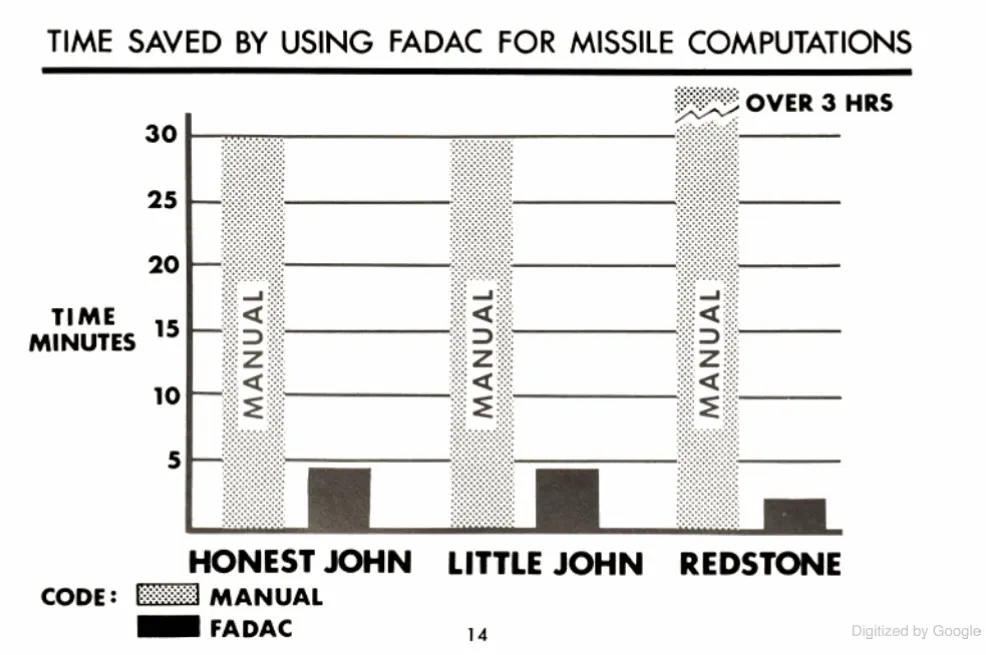

In most modern conflicts, it is artillery that causes most of the casualties. When not busy causing casualties, artillery is responsible for damaging military infrastructure and keeping enemy soldiers pinned and immobile, thus it is an essential part of all modern armies. Most artillery is used in an indirect fire role, where the gun barrel curves up to fire at a target many kilometers away. However, this presents its own difficulties in the form of aiming the gun barrel in order to accurately hit distant targets. Since the shell travels in a parabolic trajectory, one can use trigonometry to determine optimal angles for elevating the barrel. Initially, this was done using a system of complex slide rules, where someone had already done all the hard work calculating gun elevations and conditions, however the modern requirement for immense precision and longer distances than ever had made this impractical by the 50s. If one is attempting to hit a target tens of kilometers away, with sub-meter precision, many other factors like latitude, wind speed and temperature begin affecting accuracy. Accounting for these factors would result in an extremely long manual computation time, and by the 50s the US Army had begun to realize that the computers could assist in this as well. Using computers in the field to assist with aiming had been attempted with the Norden bombsight almost 20 years earlier, which had ended in unsatisfactory results and massive costs. Still, that was an analog computer, while in the late 50s incredibly powerful transistor-based digital computers had started becoming available. For this reason, the US Army revisited the idea of a computer which could accurately calculate rocket and shell trajectories, particularly for its long-range artillery platforms, such as the 155mm M1 (Long Tom) and 105mm M101. To fill this role came the FADAC – Field Artillery Digital Automatic Computer, also known in official documents as the M18 Gun Direction Computer.

Introduction to the FADAC

The FADAC itself is a marvel of engineering, particularly for late 1950s standards. It can most accurately be described as a 32-bit programmable calculator, however if going by its raw speed and capabilities it can keep up with the fastest supercomputers of the time. From official specifications, the FADAC is built with 2190 transistors, 14430 diodes, 9080 resistors, 740 capacitors and 125 other “special components” – transformers, switches, nixie, tubes, neon lamps and more. For the time, this level of integration is extremely impressive, particularly given the limitations of technology of the time. This is even more impressive given that at the time, computer science as a field of study and computer engineering hadn’t existed yet.

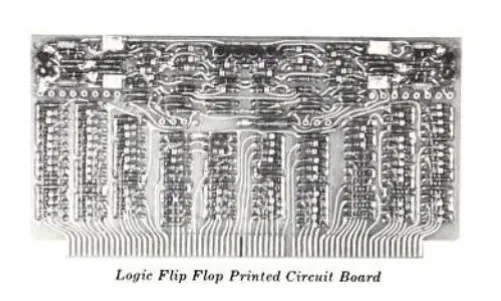

Logic family

Though official schematics, as far as I know, haven’t been released, given the number of diodes present in the system, as well as memoranda from US Army sources, and the design trends at the time, the system was most likely made with diode logic, with diode-transistor logic (DTL) intermediary amplification stages. Even though diode logic is much slower than other logic families, it was fast enough for the time and the necessary speed at which these calculations were done. Given that it would take half an hour for a human to do these calculations and humans were prone to error, particularly when under stressful situations such as war, having certainty and increased speed was a massive positive benefit.

3-in-1!

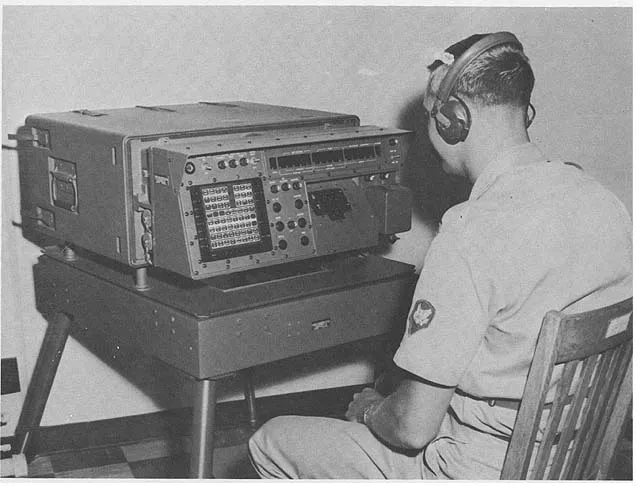

The system is built up of three main components – the FADAC main computer, the FALT test computer and the MLU magnetic tape reader. The official document released about the FADAC gives extensive notes about its reliability and ability to quickly test and diagnose the main computer. The document further mentions the focus on interchangeability and ease of repair for all the parts. The main computer is made up of 106 separate circuit boards, of which it is noted that half are flip flops. The FALT itself contains half the number of boards of the main computer, for which it is noted that nine of the 15 types of boards are interchangeable. It is also stated that the FALT can detect almost any fault of the main computer and point out the exact board that needs replacing, meaning that there should be practically zero downtime when using the FADAC, even when boards stop working. The idea of low maintenance time being an essential part of the design is something that is rarely seen in commercial electronics, and even more so in modern systems.

Hardware specs

Modern readers well versed in technology may be surprised that the FADAC is a 32-bit machine that can achieve a maximum of 12800 instructions per second. Even though by modern standards these specifications make the FADAC a glacially slow system, for the late 1950s a 32-bit system with 12800 instructions which is purely optimized for calculation, this is extremely impressive. The presence of hardware multiplication and division, although with 16-cycle latency, was also rarely seen in mass-produced computers all the way up until the 90s. Given that the fastest transistorized supercomputers at the time could achieve speeds of approximately 100000 instructions per second, the FADAC compares favorably. The comparison turns out even better for the FADAC as the arithmetic instructions are one-word, which gives it maximum throughput per instruction and means that the system in reality is bottlenecked by the memory. One thing to note is that the system runs at a nominal 460KHz, and given the instruction speed it is likely that this clock is divided by 36 internally to achieve all the necessary phases for the complex 32-bit calculations.

Storage

Modern readers might be surprised to find that the FADAC had both RAM (temporary variable storage) and ROM (program data storage) stored on one magnetic disc, an intentional decision to make both program and data memory non-volatile, something that is also rarely seen in commercial systems. Though this had downsides, such as the inherent slow speed of disc-based memory, it also made it rugged and highly tolerant to disruptions in operation. Interestingly, the disc spins at a 6000 rotations per minute, which is quite similar to modern hard drives. Added to this was a smaller magnetic disc of higher speed with a 32-word capacity – essentially a cache.

Power, bulk and eventual obsolescence

The biggest downside of the FADAC was its weight and power requirements. Requiring almost a kilowatt at 400Hz AC (standard military and aerospace frequency), the combination of a large, heavy computer and an even larger and heavier generator meant that logistics would be drastically complicated, while the noisy, heat-emitting generator would be a liability for artillery which might want to remain unspotted. Coupled with the time required to set the whole system up, the FADAC was not accepted in service and manual calculations remained for some time after. Still, the army learned from the FADAC’s development and once computers got smaller, faster and required less power, the lessons from the FADAC were applied and computers became widely used for artillery.

Sources and further reading

https://books.google.mk/books?id=mfse514lSzEC&pg=PA28&lpg=PA28#v=onepage&q&f=false http://www.ed-thelen.org/comp-hist/BRL61-f.html#FADAC https://www.themightyninth.org/War%20Stories/FADAC/FADAC.htm https://web.archive.org/web/20011002005006/https://ftp.arl.army.mil/~mike/comphist/61ordnance/chap6.html

(if some of the links don’t work, try the Internet Archive)